On January 22, 2009, U.S. District Judge Robert W. Gettleman ruled that the following Illinois law is unconstitutional:

(105 ILCS 20/1)

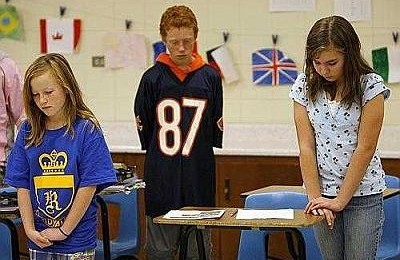

Sec. 1. In each public school classroom the teacher in charge shall observe a brief period of silence with the participation of all the pupils therein assembled at the opening of every school day. This period shall not be conducted as a religious exercise but shall be an opportunity for silent prayer or for silent reflection on the anticipated activities of the day.

(105 ILCS 20/5)

Sec. 5. Student prayer. In order that the right of every student to the free exercise of religion is guaranteed within the public schools and that each student has the freedom to not be subject to pressure from the State either to engage in or to refrain from religious observation on public school grounds, students in the public schools may voluntarily engage in individually initiated, non disruptive prayer that, consistent with the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses of the United States and Illinois Constitutions, is not sponsored, promoted, or endorsed in any manner by the school or any school employee.

ACLU Senior Staff Counsel Adam Schwartz made the untenable, irresponsible, and paranoid statement that this law “coerced children to pray as part of an organized activity in our public schools.”

On Feb. 20, 2009, IL. Attorney General Lisa Madigan appealed this ruling to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, stating that “laws requiring a moment of silence have been found constitutional in other states,” and that “the legislature debated this issue and, by an overwhelming majority, voted to enact this law (the Senate voted to enact this law by a vote of 58-1 and the House by a vote of 86-26).” (Source: Chicago Tribune Blog)

I must confess up front that I am not a huge fan of school prayer laws. The reason for my lack of enthusiasm is that the implementation of these laws makes a mockery of the seriousness and significance of prayer. For the past eight years, I worked at Deerfield High School in Deerfield, Illinois. A colleague timed our moment of silence: it was a ludicrous seven seconds.

In addition, the endless debate and controversy generated by petulant atheists, like the ubiquitous Rob Sherman, who wrongly try to strip the public square of every last vestige of our religious heritage and every manifestation of the free exercise of religious faith, serve to make students self-conscious about their faith and uncomfortable with the public spectacle that even the appearance of prayer becomes in such a hostile context.

Fortunately for students who follow a theistic faith tradition, they are free to pray anytime they choose — a truth that likely irritates many of society’s true believers: a-theists.

What troubles me more than the implementation of school prayer laws is the lack of a proper understanding of church-state relations on the part of so many Americans who have come to believe that they are legally prohibited from participation in the political process if their political decisions are shaped by religious beliefs. That issue, however, is beyond the scope of this response to Gettleman’s moment of silence ruling and Madigan’s appeal.

I am not an attorney, so the opinions offered here are those of a mere mortal, but here goes.

It seems to me that there are a number of problems with Gettleman’s recent decision. First, he makes the case “that the addition of the words ‘and Student Prayer’ to the title of the Statute conveys the true intention of the legislature to endorse and encourage prayer.” The case could easily and more reasonably be made, however, that the word “prayer” was added simply to make clear to students that prayer is permissible, an idea that many students may not realize. A reasonable case can be made that because of the pervasive cultural hostility to religion, particularly in public education, and the poor understanding that many have about church-state relations, many students may mistakenly believe that even voluntary silent prayer is prohibited.

Francis Beckwith, Professor of Philosophy & Church-Studies at Baylor University, discusses Supreme Court Justice Byron White’s response in the Wallace v. Jaffree school prayer case:

As Justice Byron White eloquently pointed out in his dissenting opinion, if more than half of his brethren would “approve statutes that provided for a moment of silence but did not mention prayer,” then where precisely would his brethren come down in the case of a teacher who answered “yes” when asked by a student if she could silently pray during the approved moment of silence? And if the giving of that answer by a state actor, the teacher, is permissible, then why is it not permissible for the Alabama legislature to provide precisely the same answer before the question is asked? Moreover, because earlier cases against school-sponsored prayer may have led some citizens to mistakenly believe that all prayer is prohibited in public schools, another purpose of this legislation is to remedy that misconception by showing that the state is not hostile to religious free exercise when voluntarily engaged in by its citizens.

The point is that moment of silence laws that include “prayer” as an option do not coerce, mandate, endorse, or embrace religion; nor do such laws constitute an unconstitutional preference of religions that practice silent prayers over those that do not, as Gettleman speciously argued the Illinois law did.

Rather, these laws communicate that the state neither prescribes nor proscribes the content of private thoughts. The inclusion of the word “prayer” is needed to clarify to Illinoisans, including students, that the state does not censor the content of thoughts, which means that prayer is permissible.

In his ruling, Judge Gettleman wrote the following:

As noted by this court in Sherman I, the clear language of the Statute compels each classroom teacher to ensure that the period of silence is used by each student only for prayer or reflection on the activities of the day ahead (“This … shall be an opportunity for silent prayer or for silent reflection on the anticipated activities of the day.”) Even silent thoughts by a student about a professional sporting event or a family vacation would appear to violate the stated intent of the Statute. The only way a teacher could be assured of compliance, therefore, would be to explain to her pupils at the opening of “every school day” that they use the period of silence for one of the two permitted purposes. Consequently, the teacher is compelled to instruct her pupils, especially in the lower grades, about prayer and its meaning as well as the limitations on their “reflection.”

The plain language of the Statute, therefore, suggests an intent to force the introduction of the concept of prayer into the schools. This is where the Statute crosses the line and violates the Establishment Clause. Prayer is without doubt “a religious activity,”

I believe Gettleman is in error when he suggests that the statute “compels” each classroom teacher to ensure that the period of silence is used by each student only for prayer or reflection.” The statute states that the moment of silence is “an opportunity” for silent prayer or reflection, which clearly indicates that neither silent prayer nor reflection on the activities of the day is mandatory. It does not say that the moment of silence is an opportunity for only silent prayer or reflection. The judge is incorrect in interpreting this clause as compelling any particular content.

Furthermore, Gettleman’s decision stated that since “silent thoughts” about activities unrelated to the day’s anticipated events violates “the stated intent of the Statute,” teachers would be required to re-teach students “about prayer and its meaning and the limitations of ‘reflection.'” This suggests three erroneous ideas: First, it suggests that wandering thoughts are a result of lack of understanding. Second, it suggests that repeated instructions are implicitly mandated to keep minds from wandering. Third, it suggests that compulsory thought control is one of the purposes of the law.

Wandering thoughts are not necessarily functions of lack of understanding; reminders and re-teaching are not implicitly mandated to compel thought-compliance; and thought control is not one of the purposes of the statute.

It is critical to understand that narrow circumscription of thought content is not the purpose — either explicit or implicit — of the law. An analogy might help illuminate this point: When schools have a moment of silence to honor soldiers killed in war, and some students think instead about the movie they saw the previous weekend, no one believes that some principle or statute is violated by their wandering thoughts. By Gettleman’s silly reasoning, the moments of silence that are now imposed in Illinois public high schools to honor those fallen in war would be considered problematic because “Even silent thoughts by a student about a professional sporting event or a family vacation would appear to violate the stated intent” of these moments of silence.

Gettleman’s decision states that “The fact that no one, not even the sternest classroom teacher, can police a child’s thoughts only reenforces the necessity for the teacher to explain the option of prayer as one of the two permitted subjects of the silent period.” But nowhere in the language of the law does it state that thoughts unrelated to the activities of the day are prohibited or that those students who choose to reflect must do so only on the anticipated activities of the day. The statute states that this moment is an “opportunity” to reflect on the anticipated activities of the day. In other words, policing thoughts is not the intent of the law and re-explanation is not the solution to drifting or divergent thoughts.

Many states have moment of silence laws that have passed constitutional muster. Let’s hope — and pray — for a judge as wise as U.S. District Judge Claude M. Hilton who ruled that Virginia’s similar law was constitutional:

The court finds that the Commonwealth’s daily observance of one minute of silence act is constitutional. The act was enacted for a secular purpose, does not advance or inhibit religion, nor is there excessive entanglement with religion … Students may think as they wish — and this thinking can be purely religious in nature or purely secular in nature. All that is required is that they sit silently.

Oh, if only Rob Sherman would choose to sit silently for a time–and perhaps even pray. . .