Statues depicting prominent figures in U.S. history have been coming down across the nation. The actions of those portrayed are being reevaluated through the eyes of some who feel their past bad deeds outweigh any of the good they accomplished, with no regard given to the common mores of past centuries. Someone living four centuries ago is held up to 21st century standards.

Some statues have been removed by local municipalities, while others have been pulled down or even decapitated and dragged into a lake. Such was the case with Union Civil War Colonel Hans Christian Heg’s statue. The statue of the abolitionist, who was killed at the Battle of Chickamauga, stood on the grounds of the Wisconsin state Capitol in Madison. In other cases, when statues were targeted for removal, it was a little more understandable – they portrayed Confederate generals and other military leaders. The removal of Heg by a violent mob made little sense. One of the mob leaders cleared up the confusion, telling the Chicago Tribune that the statue was removed because it portrayed Wisconsin as racially progressive, when slavery had never really ended but rather continues in the state through the prison system.

Viewing the protest-turned-mob leader’s words through the lens of history, one can’t help but be reminded of the Russian and French Revolutions, and even of events out of Mao’s little red book. Activists may say that suggesting such comparisons is alarmist or dramatic, but the proverbial slippery slope is there for a reason.

Now Illinois’s beloved President Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator himself, is one of the historical revisionists’ targets. Lincoln, born February 12, 1809 in Kentucky, lived in Indiana from ages 7-21, then moved to Illinois. In 1831, at age 19, he made his first flatboat trip to New Orleans. Historians believe that it was on that or another trip to the Crescent City that he witnessed a slave auction. What he saw forever changed him. Lincoln is first recorded as publicly speaking out against slavery as a member of the Illinois state legislature in 1837.

Lincoln went on to become president and was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, with the Civil War beginning just over a month later on April 12. The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued September 22, 1862, which stated that if the Confederate south did not cease its rebellion by January 1, 1863, the executive order would go into effect. When it failed to do so, 3.5 million African-American slaves held in the Confederacy were freed. Lincoln then endorsed the passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in the country as a whole.

The great orator and civil rights activist Frederick Douglass was a free black man who had escaped slavery. He met with Lincoln at the White House at least four times, but some historians believe the number was much higher. In his personal papers, Douglass said that the two men had different agendas when they first met and would argue, but they grew to be good friends. After his first meeting with the President, Douglass said to a group of abolitionists in Philadelphia, “I will tell you how he received me – just as you have seen one gentleman receive another, with a hand and a voice well-balanced between a kind cordiality and a respectful reserve.”

Was Lincoln recorded as having said things that sound racist to our ears today? Yes, he was. We know when he lived and we know he wasn’t perfect. We also know that he was leaps and bounds ahead of many in his day. He was a good man and a good president who freed the slaves. He was assassinated by the then-well-known actor John Wilkes Booth for freeing the slaves and defeating the Confederacy. Lincoln, along with 450,000 white and 40,000 black Union soldiers, gave their lives to end slavery.

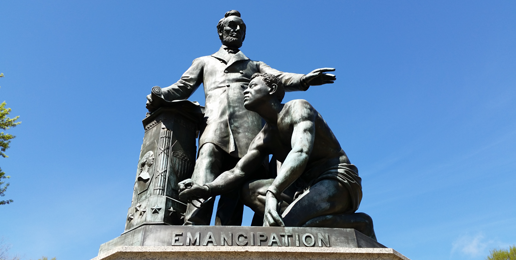

Now, students at the University of Wisconsin in Madison want to remove President Lincoln’s statue from campus because of things he said that they disapprove of and a homesteading act he signed that gave Native American land to white settlers and designated it to become the campus of their university. In Washington, D.C., protests continue to call for the removal of the Emancipation Memorial Statue in Lincoln Park. The statue, dedicated April 14, 1876, was paid for by an association of former slaves. The dedication speech was given in front of President Ulysses Grant by Frederick Douglass.

In his speech, Douglass described Lincoln’s assassination as an act of “malice” that had “done some good after all. It has filled the country with a deeper abhorrence of slavery and a deeper love for the great liberator.”

Although he developed some mixed feelings about Lincoln in the years following his death, Douglass went on to say that “no man who knew Abraham Lincoln could hate him – but because of his fidelity to union and liberty, he is double dear to us, and his memory will be precious forever.”

Much has been said about the position of the freed slave positioned next to the standing Lincoln. A reporter interviewed Marcia Cole, a member of the Female Re-Enactors of Distinction (FREED) as she stood near the statue in Lincoln Park. Cole portrays Charlotte Scott, an African-American woman from Virginia who gave the first $5 she earned towards the statue. Cole told the reporter that she was there to speak on behalf of Miss Charlotte, who would not want the statue removed.

“People tend to think of that figure as being servile, but on second look, you will see something different, perhaps. That man is not kneeling on two knees with his head bowed. He is in the act of getting up. And his head is up, not bowed, because he’s looking forward to a future of freedom.”

A bold voice for pro-family values in Illinois!

Click HERE to learn about supporting IFI on a monthly basis.