One of the things we must absolutely learn how to do better than we do is distinguish things that differ, especially things that look similar but which differ radically. We must learn to say, as Dorothy Sayers once famously said, distinguo. I distinguish.

There is a profound difference between the doctrine of interposition/lesser magistrates on the one hand and the doctrine of liberty of conscience on the other. There are places where they overlap, but there are also instances where they have nothing to do with each other. When a magistrate decides to interpose, he is doing it as a matter of conscience. But he is not exercising his liberty — he is discharging a duty.

A citizen has the right to be left alone in any number of areas. We ought not to tell him what days on which he must mow his lawn, we ought not require him to photograph homosexual unions, we ought not to tell him that the Department of Agriculture requires him to floss daily. Even if he is mistaken, and his conscience along with him, we should still let him close his shop in honor of the coming of the Great Pumpkin. What he does with his time, his money, his business is, in fact, his business.

Now in some instances, a person’s private religious convictions can become a public matter, as when the Thugs of India used their free exercise of religion in the pursuit of killing and robbing people. The point is that the exact boundaries of the liberties of every citizen is a religious issue, and is a issue that cannot be settled from up behind the Agnostic Bench. If you don’t know what truth is, then the first thing you should do is quit deciding what truths are acceptable. A Christian judge would say that the Thug’s religious liberties are a matter of no consequence. The Communist judge says that the Christian’s religious liberties are a matter of no consequence. The Agnostic judge doesn’t know what is going on, but just sits there, trying to look wise. He thinks nobody will notice, but we have.

An agent of the state occupies a different station than does the private citizen; it is a different office entirely. The law that governs his behavior cannot be neutral any more than the law that bounds the private citizen’s liberties can be neutral. Scripture asks, “Can two walk together, except they be agreed?” (Amos 3:3 ). The answer, in case you were wondering, is no.

). The answer, in case you were wondering, is no.

So that means that a society has to decide what it will allow its citizens to do and why, and what it will require its officers to do and why. The religious framework that encompasses both of these needs to be the same one. Because I am a Christian, I believe that this framework needs to be a Christian one. When it comes down to differences between Christians, and it is an area where the state must act or not act (e.g. divorce), the state must decide which of the two Christian positions is right. When they do this, they must take great care to be right. Neutrality is impossible.

Kim Davis refused to issue a marriage license to homosexuals, and she was right. But would a devout Roman Catholic, on the basis of an absolutist rejection of remarriage after divorce, have the right to refuse a marriage license to Kim Davis on one of her later marriage? I would say no, but my purpose here is not to get into that debate. My point is that the society cannot be neutral about that debate. The applicants must either be served or refused. One or the other must happen. So if we say no, and are asked why, we need to be able to say more than just because.

This is why secularism is dead on its feet. We have gotten to the reductio ad absurdum portion of the Q&A session and we are no longer bound together by a hidden-generic-protestant-north-american consensus. For decades, we thought that this consensus was what everyone “just knew.” Turns out they don’t.

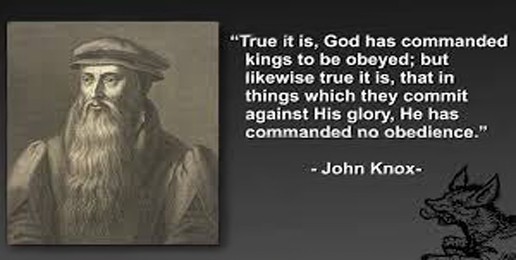

The doctrine of interposition means that Christian magistrates must be looking for an opportunity to just say no, and to do so on an issue of sufficient moral magnitude as to justify the societal dislocations that will result. Whether the municipal snowplows should run on the sabbath (and when do sabbath hours start anyway?) is not one of those issues. The two issues that I think are ripe candidates for interposition are abortion and same sex mirage. Mayors, judges, governors, county clerks, etc. should simply refuse to cooperate with evil mandates concerning them, and should issue decisions of their own restricting them. A Christian governor should simply outlaw abortion in his state.

Some are concerned that this would lead to a shooting war, but I don’t think that is necessary at all. If the feds send in the troops to keep the abortion clinics in Texas open, then another three states should follow suit and ban abortion. They can’t put everyone in jail. The Civil Rights movement didn’t lead to a shooting war. All that is necessary for this to become completely unwieldy for the bad guys is for enough good guys to say enough. As Edmund Burke might put it, were he here, all that is necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to have reservations about the doctrine of interposition.

These issues — abortion and same sex mirage — are good issues. They are weighty issues, whether weighed in the balances of Scripture, nature, or history. They are pressing issues — everyone knows a great deal about both of them. They are issues where victory is actually attainable. If everyone who objected to abortion acted like it, it would be gone this time next week. The same thing is true of same sex mirage.

The problem is not that we don’t have enough people who object. The problem is that those who object are so darn sweet. The problem is not that we don’t have enough resources. Our problem is that we won’t use what we have.

And so in the meantime it is fully appropriate for us to be fighting for “carve outs” in the law for private citizens. Pacifists shouldn’t have to fight in the army, and evangelical photographers and bakers should not be forced to celebrate abominations. But officers have a duty to interpose. They have a duty to prevent. A photographer should accept the carve out when it is offered. The official should not. For an officer of society to ratify high disobedience to God is as much compromise as would be exhibited by a florist who celebrated a same sex reception.

The secularist says that if you are not willing to issue a license to a same sex couple, then you should resign the position. I say something that sounds similar, only reversed. I would say that if you are not willing to interpose, you should resign the position. Why? Because you are not willing to fulfill the obligations that God assigned to that office. It is the will of God that all lesser officials, all lesser magistrates, hold their offices in the fear of God, which means that they must be willing to interpose when the greater magistrates mandate broad social rebellion.

And that is exactly where we are right now. We need leaders, at every level, who will refuse to participate in the rebellion.

This article was originally posted here