It’s Simple: Just Invite the Socialist to Talk

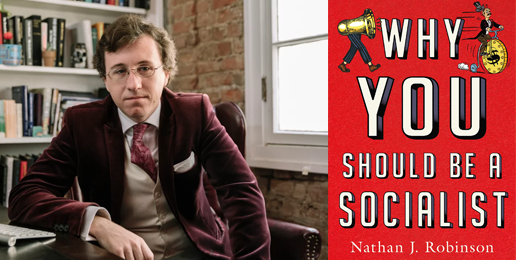

Isadore Johnson is a libertarian-leaning student at the University of Connecticut and a member of Young Americans for Liberty. Last fall, he asked Nathan J. Robinson, author of Why You Should Be A Socialist and Editor-in-Chief of the left-wing political journal Current Affairs, if he would answer a series of questions about socialism and capitalism for the university newspaper. Robinson obliged and you can read it all at Q&A With A Conservative Student on Socialism.

It’s rather long, but it’s worth reading carefully because Johnson has given us an excellent model to follow. Most political discussions across ideological divides amount to little more than two people talking past one another–opposing sides pushing their positions but giving little or no thought to the other. By contrast, what Johnson did is exactly the opposite. Seeking first to understand, he invited his ideological opponent to explain his position and elaborate at will.

And elaborate, he did. Following are a few points that came out. The statements in bold are my summations. The quotes aren’t meant to be scare quotes, but to draw out what Robinson said in his own words:

There is no definition of what socialism actually is. But this is not just a matter of socialists having disagreements. Disagreements are part of any political program. It’s that socialists have no objective grounding on which to define a political program. Socialism is primarily based on subjective feelings and desires about how socialists want the world to be, not objective facts about how it really is. Robinson thinks of socialism as a “sense of outrage” he feels when people are exploited or abused, and he said socialists don’t want people to go without their basic needs being met. Yet when he was asked for specifics about how these well-intended desires might be implemented, his answers took the form of “this is not a question with one answer,” “we do not yet know,” and “line-drawing is always hard.”

Socialism is based on feelings. Decent people of all political persuasions agree with his sentiments and understand that policymaking is complex and will often be a work in progress. But the problem of socialists’ inability to define their own program, let alone propose policy to implement it, is not just a matter of a few details to be worked out. The bigger problem is that socialism confuses subjective feelings for objective moral principles. This is a fundamental category mistake.

“Socialist ethics are feelings,” Robinson said. “I think of [socialism] first as a kind of instinctive egalitarian feeling.” He just assumes that his feelings constitute, ipso facto, “the principles of socialism,” and beyond that, the matter is not up for debate. “We’re saying that given that the principles of socialism are clearly sound, we have a question about how best they can be achieved. I think this is the right kind of uncertainty to have. I want the debates in the country to be about how socialist values are best put into practice, not about whether they themselves are good.”

No, this is exactly the wrong kind of uncertainty to have. Not only does he not want to discuss whether his “values” are, in reality, sound or good, he all but admitted that he doesn’t recognize any foundation for morality to begin with. Nor does he care to. This came out when Johnson asked him about rights. “Rights are a complicated question,” he responded. “Where do they come from? Are they simply conventions? Did human rights exist before people recognized them to exist? This gets us into the entire foundation of morality and I can’t begin to go into it here.” Respectfully, if he can’t identify this starting point, the rest of us are right to be wary about where he’s headed. Which leads to our third observation.

The remedies socialism proposes start out vague. Then, to the extent that they get specific, they are alarming. “Socialism means common ownership,” Robinson writes. He said he likes “decommodified things.” Here are some things that he wants “provided for all equally”: food, housing, education (including college), healthcare services, gyms, and swimming pools. These are things that should not be bought and sold. “I prefer a ‘commons’ because markets … are at the very least burdensome.” Before he’s done, he’s all but said he’d like everything to be free. “It’s a much worse experience when everything is commodified. Getting to roam freely without thinking about money is wonderful, which is why I’m in favor of robust commons.”

It’s one thing to say that you’d like everything to be free (wouldn’t we all?). It’s quite another to make that happen. The closest Robinson came to explaining how this might be done is to refer to the ideas of two socialist thinkers. He mentioned Fredrik DeBoer, who suggests “making it so that things aren’t ‘traded,’” and David Schweickart, author of After Capitalism, who argues for a kind of socialism by which “we just alter who owns the stuff.”

Robinson rattled off those two ideas and then blithely went on. But right there, he exposed the only way his “utopian concept” can come about: by altering “who owns” things. Outside of leftwing fog zones, this is known as theft. Food, housing, education, healthcare services–these things are the products of labor, in some cases highly skilled labor. They do not just “exist” somewhere in somebody’s warehouse, waiting to be distributed. They must be cultivated, built, or produced, which requires significant expenditures of input and effort. Socialists often talk about capitalists’ greed, but it is the socialist who wants to reap the rewards of other people’s labor without having to work for them, and to own “the stuff” that used to belong to other people without trading anything for it in return. This is the textbook definition of greed.

The best instrument for clearing up fog is sunlight. Similarly, the best way to expose the underbelly of socialism is to invite a socialist to explain it in as much detail as you can draw out. He may want to “own” other people’s stuff, but what the smart capitalist will do is make him “own” his own agenda.

If you appreciate the work and ministry of IFI,

please consider a tax-deductible donation to sustain our endeavors.